Our need to be inspired by storytelling in our modern permacrisis.

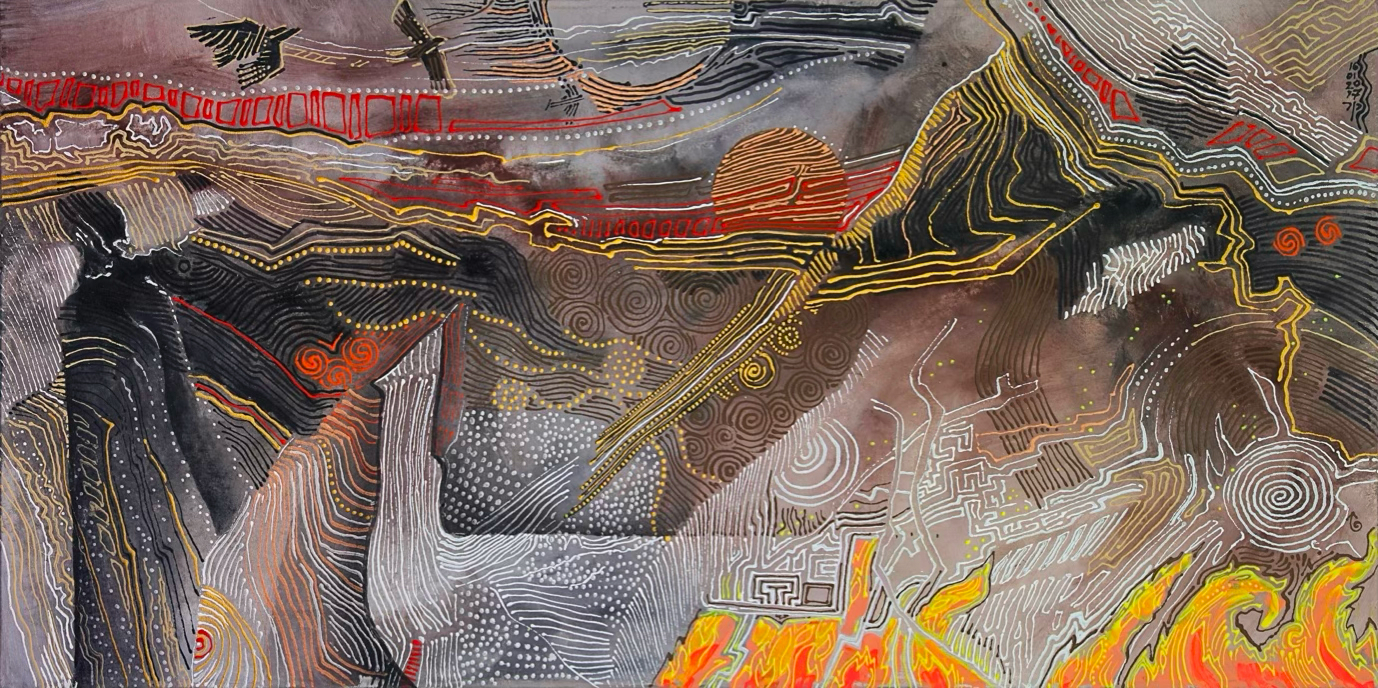

In 2019, Australian Aboriginal elders from the Yuin Nation gathered with locals and visitors around a campfire on the New South Wales coast. They shared stories of the land’s history, not just as cultural heritage but as practical knowledge. One elder spoke of the ancient practice of “cool burning” – low-intensity fires used for thousands of years to manage the landscape, prevent catastrophic bushfires, and promote biodiversity. It was a stark contrast to the devastating wildfires that would sweep across the region months later. Their stories weren’t just about the past; they were a guide for navigating the future.

Today, as we stand at a climate crossroads, we need those stories more than ever. But not the ones of doom that paralyse us or the utopian dreams where technology magically saves the day. We need something in between: a thrutopia, a narrative thread showing how we navigate the messy, challenging path through this moment, step by step.

Ancient myths weren’t just entertainment; they were survival guides. Greek tragedies warned of hubris, Native American campfire tales taught ecological stewardship, and Aboriginal Dreamtime stories mapped the land itself. These narratives connected people to the rhythms of nature – a connection industrialisation has largely severed, pushing us towards ecological collapse.

Consider the Norse myth of Ragnarök. It’s not just an end-of-the-world tale; it’s a story of transformation. As the world burns and the gods fall, a new earth rises from the ashes. Crucially, enemies fight side by side, gods and giants united by necessity. It’s a reminder that overcoming the challenges of a changing climate will demand unlikely alliances and collective effort, not finger-pointing and division.

The Hopi, a Native American tribe from the southwestern United States, have a prophecy known as Powateoni, or the time of purification. This prophecy speaks of a time of chaos and imbalance, a period of Koyaanisqatsi, where the natural world and human life are out of harmony. However, it also foretells that renewal is possible, but only if people choose the right path forward.

Similarly, the Ojibwe, an Indigenous people primarily from the northern Great Lakes region of North America, have their own prophecy called the Seventh Fire. According to this prophecy, humanity stands at a crossroads, with two paths ahead – one lush and green, the other barren and scorched. The challenge, as the Ojibwe see it, is not just to choose the greener path, but to walk upon it with respect, so that we do not destroy it by continuing the patterns of overconsumption that have led to imbalance in the past.

Explorer Robert Swan once said, “The greatest threat to our planet is the belief that someone else will save it.” He’s right, but the danger goes deeper. It’s not just about who will act, but how we frame what we’re facing.

This isn’t a problem we can fix and move on from. It’s a predicament we must live through.

A problem has a solution. It can be solved, completed, set aside. But a predicament is ongoing. It demands resilience, not resolution; adaptation, not quick fixes. The climate crisis is not something we’ll ‘solve’ in any simple, singular way, it’s something we’ll have to navigate, together, for the long haul.

Contemporary thinkers are beginning to echo these ancient insights. Economist Robert Shiller has shown how narratives shape human behaviour and, by extension, economies and policies. The stories we tell about our climate crossroads can either paralyse us with fear or inspire us to act. Albert Camus’ interpretation of the Sisyphus myth offers another lens: Sisyphus, eternally condemned to push a boulder up a mountain, knowing that it will inevitably roll back down, finds his true meaning not in the achievement of the task, but in his defiance of futility. For Camus, the myth of Sisyphus is not one of despair but of profound rebellion, a recognition that, even in the face of an insurmountable challenge, there is value in the struggle itself.

In many ways, this mirrors our own climate and ecological crisis. The task before us seems insurmountable; every step forward often feels undone by the forces of consumption and environmental degradation. Yet, like Sisyphus, we are called not to abandon the effort, but to find purpose in perseverance. It is the act of rising each day to face the challenge, to make deliberate choices in the face of overwhelming odds, that gives us meaning. The path ahead will indeed be fraught with hardship, but as Sisyphus teaches us, the effort to push the boulder forward, despite knowing it may roll back, is where the true significance lies.

A New Kind of Storytelling

The stories we tell about our future are not merely reflections of our hopes and fears; they are the architects of the world we are shaping. Just as our inner narratives drive our actions and decisions, the future we envision influences how we think, vote, invest, and innovate. When we are fed only tales of doom, we risk succumbing to inertia and despair, immobilised by the overwhelming nature of the challenges before us. On the other side, if we cling solely to stories of miraculous salvation, where a new technology or policy or revolution appears as a total panacea, we open the door to complacency, waiting passively for a solution to arrive.

What we need, then, are thrutopias: narratives that neither deny the difficulty of the road ahead nor offer a simplistic resolution. These are stories that acknowledge the hard, uncertain journey yet guide us toward a way through, inspiring action through a vision that is as rooted in reality as it is in possibility.

Science fiction writer Kim Stanley Robinson has explored this middle ground in his novel The Ministry for the Future, which imagines a future shaped by both catastrophe and collective action. His story doesn’t pretend the transition will be easy, but it insists that a just and sustainable world is possible. Similarly, Rebecca Solnit argues that hope is not about blind optimism but about belief in the possibility of change, even in the face of uncertainty.

In our view, the best climate thrutopia we yet have is Stephen Markley’s astonishing epic of the coming two decades, The Deluge. This very gritty yet ultimately redemptive novel gives us a sense of what is possible, and of how the various struggles we are engaged in right now could yield a much greater prize.

And there are real-world thrutopias taking shape right now, too. Indigenous-led conservation projects, regenerative agriculture movements, and cities transitioning to clean energy all offer glimpses of what’s possible. These aren’t utopian fantasies; they are imperfect, ongoing efforts to live within planetary boundaries while ensuring human flourishing.

Just as the campfire stories shared by Aboriginal elders were not mere relics of the past but vital guides for survival, we too must weave narratives that help us navigate the climate crossroads we face. The stories we need are not those that simply ask what will happen, but those that challenge us to consider what we will do. They must acknowledge the grief and loss that come with this crisis, but also remind us of our agency and capacity for action. Like Sisyphus, our struggle, though difficult and often seemingly futile, is meaningful, not because we are guaranteed to reach the summit in our lifetime, or ever, but because the effort itself is part of the journey.

The path ahead is uncertain, but it is not wholly unknowable. As the elders before us did, we can tell stories that light the way, stories that inspire, galvanise, and guide us through the challenges, helping us find purpose in the struggle and strength in our collective resolve. The narratives we choose today will determine not just how we face the future, but how we shape it together.